Strategic Plan

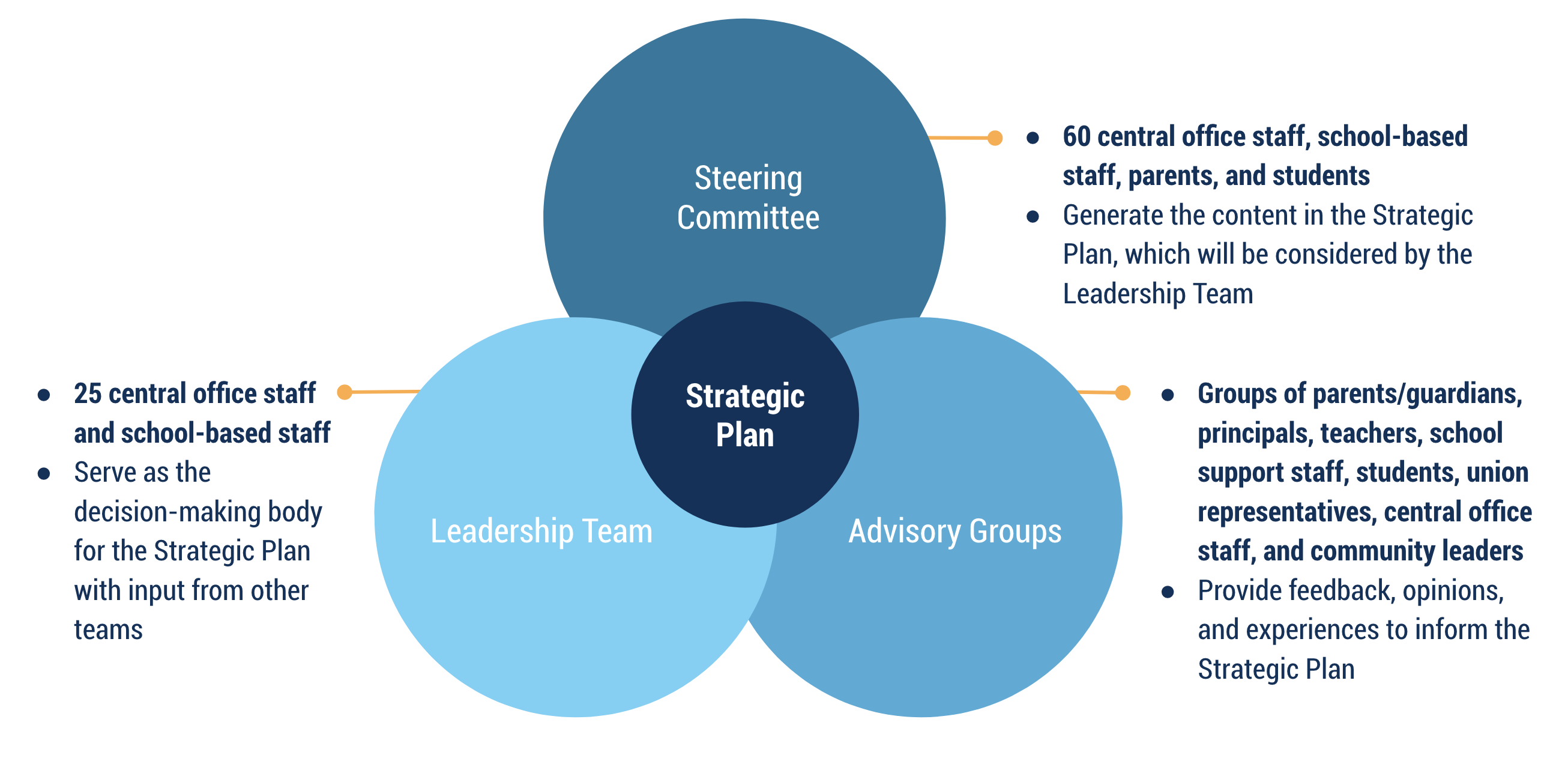

The Strategic Planning Process kicked off in December 2022 and will conclude with the approval of the 5-year Strategic Plan at the May Board of Education Public Meeting. This process includes several key phases to develop the components of the plan and allow for feedback and insights from the Advisory Groups.

Stages of the Strategic Planning Process

Mission, Vision, and Core Values

During the first stage of the Strategic Planning process, the District’s core values, vision, and mission were refined. These elements will serve as the foundation for the Strategic Plan and our work going forward. Parents, students, community members, and staff were asked to provide feedback as these elements were updated. All members of the community were invited to complete a Mission, Vision, and Values survey so that the revisions reflect the viewpoints of the entire District. In addition, all 8 Strategic Planning Advisory Groups met to discuss their insights and feedback on the mission, vision, and values. Both the survey participants and Advisory Group members reviewed a range of options and examples to elevate themes and ideas that were the most meaningful to them. Below is a summary of the individuals and Advisory Groups that provided feedback.

District-Wide Survey Participants

984 individuals completed the survey

- 68% Parents/Guardians

- 14% School-based staff

- 7% Students

- 7% Central Office staff

- 3% Community members

Advisory Groups

- Central Office Staff

- Community Leaders

- Parents/Guardians

- School Leaders

- School Support Staff

- Superintendent’s Student Advisory Council

- Teachers

- Union Leaders and Representatives

Revised Values, Vision, and Mission

Based on the survey feedback and the insights from the Strategic Plan Advisory Groups, Steering Committee, Leadership Team, and the Board of Education, we have completed the revision process of the District’s mission, vision, and core values. We worked to incorporate ideas and themes that were frequently highlighted across multiple groups and perspectives. With such a wide range of feedback, not every insight was elevated, but efforts were made to create a mission, vision, and core values that is as inclusive of our shared ideas as possible. We hope that these will serve as a strong foundation for our work going forward and thank everyone for their time and effort in this revision process. Below are our updated core values, vision, and mission for the School District of Philadelphia.

Core Values

- Safety is imperative to our work.

- Equity requires needs-based distribution of resources.

- Collaboration involves gathering and honoring community voices.

- Joy inspires active engagement and belonging.

- Trust is built through good communication, public transparency, and holding ourselves accountable.

- Ambition requires us to work with urgency to accelerate student achievement.

Vision

To prepare students to imagine and realize any future they desire.

Mission Statement

All sectors of public education in Philadelphia will work with urgency to provide every student with the opportunity to achieve positive life outcomes in partnership with diverse families, educators, and community members who are valued and respected.

Summary of Feedback

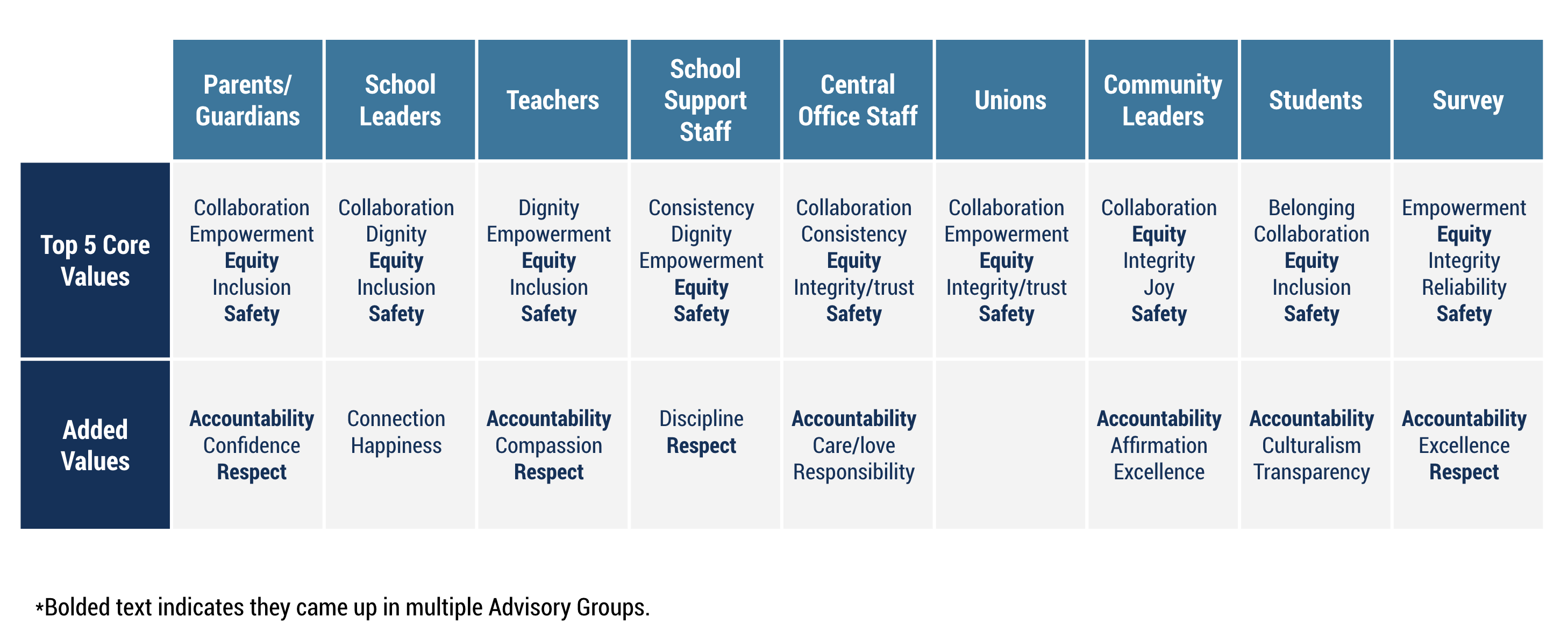

The results of the Mission, Vision, and Values survey and the feedback from the Advisory Groups were analyzed for common themes and insights. There were many places of agreement, while in other areas we heard differing opinions. For the core values, survey participants and Advisory Group members were asked to identify which listed values resonated most with them and if there were any missing. Here is a summary by group of the values that were elevated and suggested.

Core Value Themes By Participant Group

Click here to view image larger

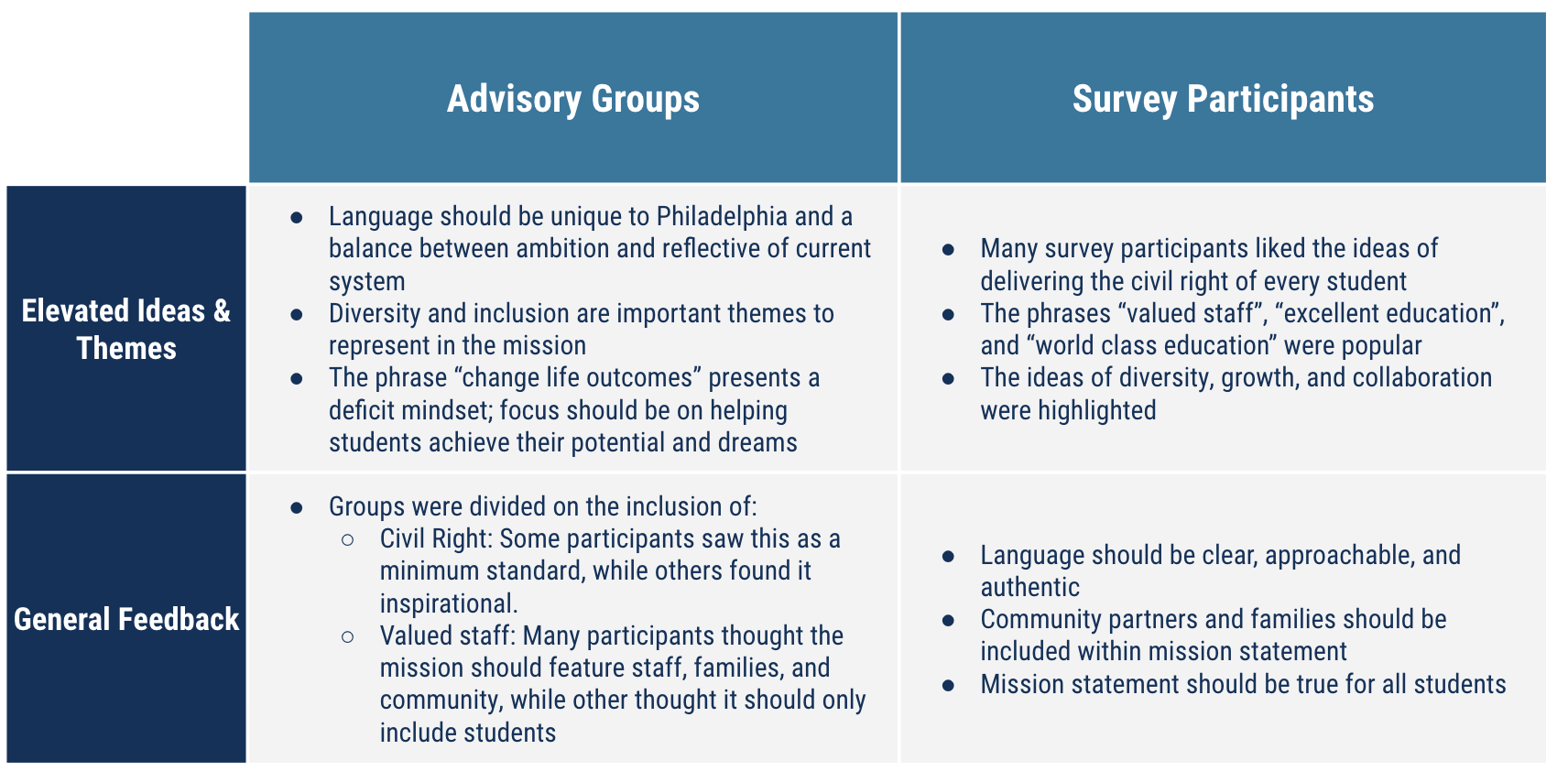

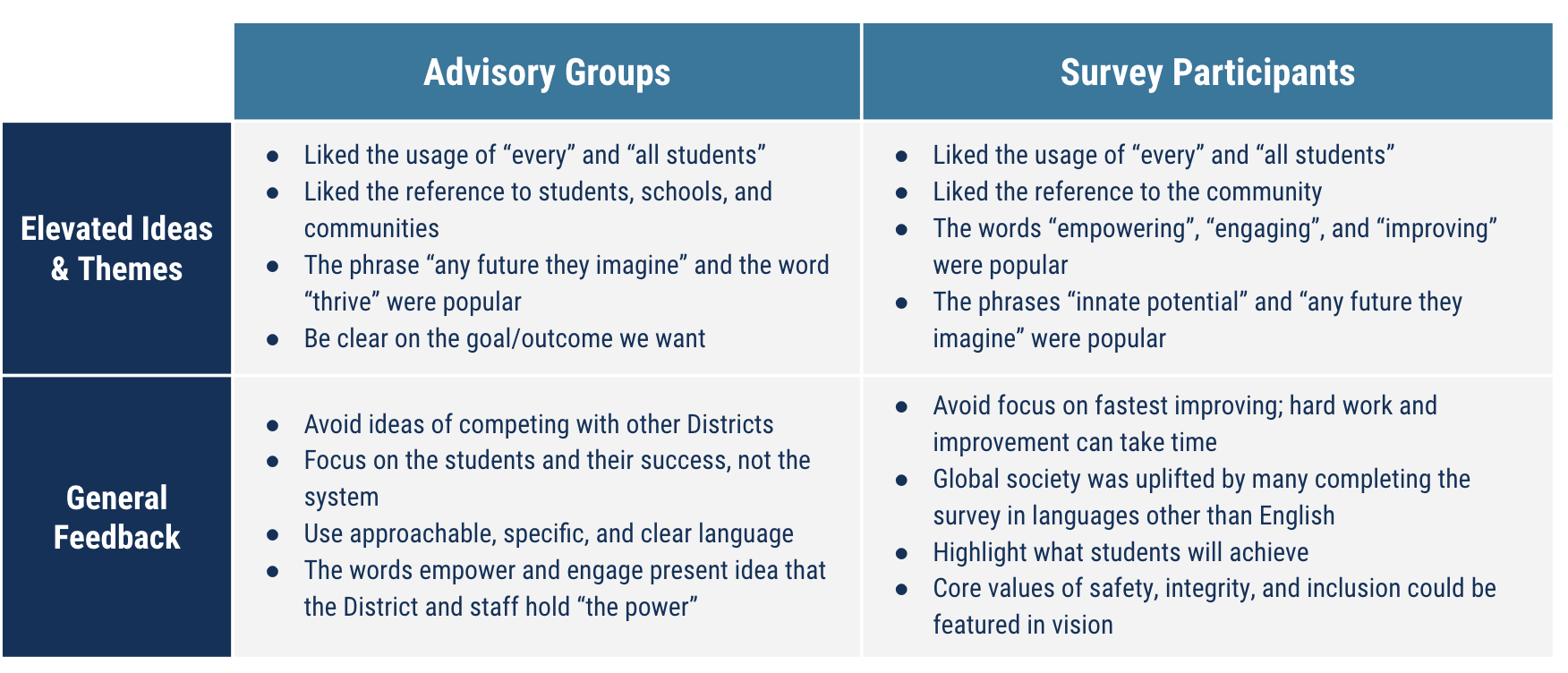

In reviewing examples of vision and mission statements, Advisory Group members and survey participants shared which ideas, words, and phrases resonated with them, as well as general feedback to keep in mind.

Vision Feedback Themes

Click here to view image larger

Mission Feedback Themes

Theory of Action

As the next Stage in the Strategic Plan, the Advisory Groups, Steering Committee, and Leadership Team provided feedback and insights to generate a theory of action. The Transition Team Report noted that the District lacked a clearly outlined theory of action on how it expects to raise student achievement. This newly created theory of action documents how we as a District plan to improve and accelerate progress towards our goals.

When we focus on…

Then we will reach the Goals and Guardrails and transform learning and life outcomes for all students.

Priority Area 1

Priority Area 1

Improve safety and well-being (physical, social-emotional, and environmental)

Safe environments are critical for our students and staff to learn and grow. This includes physical, social-emotional, and environmental safety. To make strides in these areas, our approach must be collaborative – including the District, the City of Philadelphia, and our partners throughout the community. As these Strategic Actions are implemented, students, staff, and families will see improvements in physical learning spaces, more consistent access to mental and behavioral health services, greater social-emotional supports, and an increased sense of safety in school buildings.

Strategic Actions

1.1 Establish a facilities master plan project team, including internal and external stakeholders, to identify a process and investments needed to significantly improve academic achievement and to achieve Guardrails 1 and 2.

1.2 Improve management of environmental conditions and hazards by hiring an administrator and investing in a modern data management system.

Why is this urgent?

Our students’ perceptions of building conditions are related to their feelings of belonging, safety, and trust at their schools. During Listening and Learning sessions, students, school staff, families, and community members shared serious concerns about lead and asbestos remediation, lack of air conditioning, and needed upgrades to electrical and security systems in school buildings. A 2017 report estimated the replacement value to facilities across the district to be $7.8 billion dollars.

Why these strategies?

Spatial configurations impact students’ and teachers’ ability to perform. To maximize learning, students need clean air, good light, and a quiet, comfortable, and safe learning environment. High quality teachers tend to transfer to schools with better facilities when given the opportunity. Additionally, a recent study found that school facility improvements in Los Angeles had a positive impact on test scores and attendance, yielding a strong return-on-investment of $1.62 for every $1 spent.

Aligns with: All Goals, Guardrails 1 and 2; Transition Team Recommendations

1.3 Replace all analog security cameras at 150 schools.

1.4 Pilot and evaluate Opengate weapons detection technology for stand-alone middle schools.

Why is this urgent?

Philadelphians believe that Dr. Watlington’s first priority as Superintendent should be school climate and safety. In 2022, Philadelphia recorded over 15,000 violent crime offenses, including over 4,000 shooting incidences.District stakeholders feel that, at the most basic level, school building doors, locks, and cameras are essential for security, yet they are not always functioning properly. On the annual survey, only 55% of students reported that they feel safe in their school hallways.

Why these strategies?

Safe schools are places where students are safe from violence, bullying and harassment, and the influence of substance abuse. Decades of research have shown that when students do not feel safe in school, they suffer socio-emotionally, behaviorally, and academically. Internal research shows that teacher retention is linked to teacher perceptions of school climate and safety. Working cameras outside of the school building have been shown to improve students’ perceptions of safety. The Opengate technology identifies threats to safety by detecting specific types of weapons, such as assault rifles (it is not designed to detect lesser threats, such as knives).

Aligns with: Guardrail 1

1.5 Expand the Safe Path Program in partnership with foundations and city and state funders.

Why is this urgent?

On the annual survey, 51% of students indicated that they have safety concerns going to or from school. Over 60% of students said they do not feel safe in the neighborhood surrounding their schools. Two-thirds of leaders said that neighborhood crime/safety is a challenge to student learning. During Listening and Learning sessions, students noted that neighborhood crime/safety impacts their ability to attend school.

Why this strategy?

Research on the Safe Passage Program in Chicago found that it had a significant impact on reducing crime near schools. It is an important component of addressing stakeholder concerns, including students having to travel far distances and through unsafe conditions to get to their school, which is a barrier to regular, on-time attendance.

Aligns with: Guardrail 1; Transition Team Recommendations

1.6 Develop a bridge program for students transitioning back from placement at Philadelphia Juvenile Justice Services Center, Pennypack House, and other long-term placements.

Why is this urgent?

Over the past two school years, approximately 1,000 students transitioned back to a general education setting from long-term facilities, dependent placements, or mental health hospitals. These students are more likely to have experienced trauma and neglect and more than twice as likely to drop out of school than students who have not been sent to an alternative setting. However, when formerly incarcerated youth return to and attend school regularly, they reduce their chances of reincarceration and dropping out. Themes from Listening and Learning sessions with school leaders indicate a need to improve the coordination of services for students returning from placement, including collaboratively identifying the school that can best meet the needs and interests of each student and ensuring that every student is fully supported in adapting to and thriving in the new environment. School leaders also noted that transitional supports often do not last long enough to meet the extensive needs of returning students. Ideally, school leaders would like students to have the opportunity to participate in interim programming aimed at supporting their transition back to the general education setting.

Why this strategy?

Students returning from long-term placement benefit from high levels of adult support and service coordination, which schools do not always have the capacity to provide. Supportive interventions, such as mentoring and restorative practices, can have a positive effect on attitudes about school for students who are transitioning back from a long-term placement. For students with intensive needs, educational programs that can “bridge” the gap between a long-term placement and a traditional learning environment can focus on providing these supports in order to fully prepare the learner to return to a traditional school setting.

Aligns with: Goal 4 and Guardrail 1

1.7 Identify, audit, and improve school climate programs.

Why is this urgent?

National research strongly links school climate with student attendance, academic achievement, persistence to graduation, and teacher attendance and retention. In the District, when accounting for school-level student demographics, responses to climate questions on the student, parent/guardian, and teacher surveys were all significantly predictive of school-level math and reading proficiency. Fewer than half of student respondents on the annual survey indicated that they consistently feel like they belong at school (36%); feel welcome at school (45%); and enjoy being at school (31%). This is particularly concerning given that there is a strong link between academic achievement and how students feel in school. Evidence-based social-emotional and climate programs can significantly improve overall climate and students’ positive feelings about school; however, implementation data reveals that many schools struggle to implement these programs with fidelity.

Why this strategy?

The District currently supports three evidence-based school wide social-emotional and restorative climate approaches: Culturally Responsive Relevant Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (CR-PBIS); Schoolwide Social-Emotional Learning (SEL), and Relationships First (RF). Schools select their schoolwide approaches during the school planning process. When PBIS is implemented with fidelity, there are positive outcomes for students, such as reductions in suspensions and truancy, and gains in reading and math achievement. Schoolwide SEL practices in schools provide short- and long-term benefits to students’ well-being, prosocial behaviors, and avoidance of high-risk behaviors (e.g. substance abuse). These impacts persist regardless of parental income or race. The Relationships First program, which was modeled after Oakland Unified School District’s restorative justice program, is associated in multiple studies with decreases in suspensions, expulsions, and referrals for violent offenses, and with large gains in academic achievement. Strong implementation of these programs can be expected to improve outcomes in all of these areas.

Aligns with: Guardrails 1 and 4

1.8 Identify, audit, and improve mental and behavioral health services in partnership with the City of Philadelphia.

Why is this urgent?

Exposure to chronic childhood trauma significantly increases the risk of developing mental health disorders, which in turn negatively impact academic achievement. Results of the Philadelphia Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) show that over 39% of District students have experienced traumatic events, including witnessing physical abuse in their home and violence in their community. Nearly all school leaders (91%) identified mental health as a significant challenge in their school, according to the annual survey. In addition, during Listening and Learning sessions, students, school staff, families, and community members shared that the District has insufficient staff to meet students’ mental health and social-emotional needs, particularly in the midst of Philadelphia’s gun violence epidemic. Schools need more trauma-informed approaches, more counselors, and more caring adults to listen and understand students’ experiences.

Why this strategy?

The Institute of Education Sciences has identified several trauma-informed mental and behavioral health services that have promising evidence when implemented with fidelity. They can improve outcomes for students, including the reduction in trauma- related symptoms. Several of these evidence-based programs are currently being implemented by the District, but we have yet to evaluate implementation or effectiveness.

Aligns with: Guardrails 1 and 4

1.9 Recruit and retain certified school nurses for all schools to provide in-person or telehealth services depending on student need.

Why is this urgent?

Chronic health conditions are a barrier to learning for many District students. On the Philadelphia Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), 25% of high school students reported being told by a doctor or nurse that they had asthma, and 34% reported that their physical health was not good. Echoing this self-reported data, in the annual survey, 40% of school leaders reported that chronic illness was a great or moderate challenge to student learning. Recognizing the severity of health-related barriers to learning, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) PolicyLab recommended that the District implement more optimal school nurse staffing models and supports to adequately respond to the volume and complexity of our students’ health needs. Over the past three years, the District has had a year-end nurse vacancy rate of between 3% and 6%.

Why this strategy?

The presence of a full-time school nurse is associated with reduced absenteeism and missed class time, particularly for students with asthma, students living in poverty, and African-American students. Emerging research shows that when in-person nurses are not available, telehealth services can be a valuable resource for expanding access to health services, which can result in better management of chronic conditions, improved education, reduced travel time and expenses, and fewer absences from school and work.

Aligns with: Guardrails 1 and 4; Transition Team Recommendations

1.10 Implement Breakfast After the Bell at all schools and offer sufficient, healthy, and appetizing food during appropriate meal times to all students.

Why is this urgent?

Food-insecure children are more likely to have lower grades and test scores and to experience developmental delays, social-emotional and behavioral problems, and suspensions. District families report double the rate of food insecurity compared to state and national averages. On the annual survey, 41% of principals identified food insecurity as a great or moderate challenge to student learning. During Listening and Learning sessions, students, school staff, families, and community members shared that hunger is a challenge to student learning, and that not all District students have equitable access to healthy and appetizing school food. Students also noted that access to appetizing food promotes regular student attendance. On the annual survey, 48% of students disagreed that their school lunch tastes good and 44% disagreed that they got enough food to fill them up. Although all schools serve breakfast and lunch at no cost to families, participation varies due to meal timing and student perceptions of food quality and taste. District research found that students encounter barriers to getting to school early enough to access free school breakfast prior to the start of school. Additionally, lunch schedules vary from as early as 9:30am to as late as 1:30pm. When breakfast and lunch intervals are not aligned well, this can mean that students are hungry while in class.

Why this strategy?

There are positive associations between school meal programs, including Breakfast After the Bell, and improved diet quality and food security, increased academic performance and attendance (particularly for food-insecure or malnourished students). District research found increased breakfast participation rates in schools with Breakfast After the Bell programs. Additionally, principals and school staff believe that offering popular items, such as fresh fruit and hot breakfast foods (e.g., egg sandwiches) increases breakfast participation. Ensuring that students have adequate time to eat at appropriate times during the school day means they have the energy needed to focus on learning.

Aligns with: Guardrails 1 and 4

1.11 Implement recess supervised by trained staff and aligned to national best practices for all K-8 students.

Supporting Research

1. Race equity and inclusion action guide: 7 steps to advance and embed race equity and inclusion within your organization. (2014). Annie E. Casey Foundation. https://assets.aecf.org/m/resourcedoc/AECF_EmbracingEquity7Steps-2014.pdf#page=4.

2. Guardrail 1: Every school will be a safe, welcoming, and healthy place where our students, staff, and community want to be and learn each day. This means that our schools will be: 1) environmentally safe and clean; and 2) spaces with inclusive climates that provide students with access to robust social, emotional, and mental health supports.

3. McCrossan, E., Pylvainen, H. (2023). Summary of high-level findings from cognitive interview focus groups with students about District-Wide Survey questions related to Guardrail 1: Safe and Supportive Environments. School District of Philadelphia. Internal memo.

4. Reitano, A., McCrossan, E., Fornaro, E., Pylvainen, H., Lesnick, J., and Wolford, T. (2023). Highlights of key findings from the Superintendent’s Listening and Learning Tour. School District of Philadelphia. https://www.philasd.org/ research/2023/01/23/highlights-of-key-findings-from-the-superintendents-listening-and-learning-tour/.

5. Parsons Environment & Infrastructure Group Inc. (2017). School District of Philadelphia Facility Condition Assessment. Parsons Corporation. https://www.philasd.org/capitalprograms/wp-content/uploads/sites/ 18/2017/06/2015-FCA- Final-Report-1.pdf.

6. Schneider, M. (2002). Do school facilities affect academic outcomes? (ED470979). US Department of Education Review. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED470979.pdf.

7. Feng, L., & Sass, T. R. (2017). Teacher quality and teacher mobility. Education Finance and Policy, 12(3), 396–418. https://doi.org/10.1162/EDFP_a_00214.

8. Feng, L. (2018). Hire today, gone tomorrow: New teacher classroom assignments and teacher mobility. Education Finance and Policy, 5(3), 278–316.

9. Lafortune, J., & Schönholzer, D. (2022). The impact of school facility investments on students and homeowners: Evidence from Los Angeles. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 14(3), 254–289.

10. Reitano, A., McCrossan, E., Fornaro, E., Pylvainen, H., Lesnick, J., and Wolford, T. (2023). Highlights of key findings from the Superintendent’s Listening and Learning Tour. School District of Philadelphia. https://www.philasd.org/ research/2023/01/23/highlights-of-key-findings-from-the-superintendents-listening-and-learning-tour/.

11. Philadelphia Police Department. (n.d.). Crime Maps & Stats. https://www.phillypolice.com/crime-maps-stats/.

12. Reitano, A., McCrossan, E., Fornaro, E., Pylvainen, H., Lesnick, J., and Wolford, T. (2023). Highlights of key findings from the Superintendent’s Listening and Learning Tour. School District of Philadelphia. https://www.philasd.org/ research/2023/01/23/highlights-of-key-findings-from-the-superintendents-listening-and-learning-tour/.

13. Internal data, Qlik Philly School Experience Survey Application, Accessed May, 2023.

14. National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments. (n.d.). Safety. School Climate Improvement: Safety. https://safesupportivelearning.ed.gov/topic-research/safety.

15. Ripski, M. B., & Gregory, A. (2009). Unfair, unsafe, and unwelcome: Do high school students’ perceptions of unfairness, hostility, and victimization in school predict engagement and achievement? Journal of School Violence, 8(4), 355–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220903132755.

16. Bradshaw, C. P., Cohen, J., Espelage, D. L., & Nation, M. (2021). Addressing school safety through comprehensive school climate approaches. School Psychology Review, 50(2-3), 221–236.

17. Bryk, A., Sebring, P. B., Allensworth, E., Easton, J. Q., & Luppescu, S. (2010). Organizing schools for improvement: Lessons from Chicago. The University of Chicago Press.

18. Temple, J. & Reitano, A. (2020). The relationship between teachers’ perceptions of school climate and teacher retention. School District of Philadelphia, Office of Research and Evaluation. https://www.philasd.org/research/ wp-content/uploads/sites/90/2020/07/Teacher-Perceptions-of-Climate-and-Retention-Research-Brief-July-2020.pdf.

19. Johnson, S. L., Bottiani, J., Waasdorp, T. E., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2018). Surveillance or safekeeping? How school security officers and camera presence influence students’ perceptions of safety, equity, and support. Journal of Adolescent Health, 63(6), 732-738.

20. CEIA Opengate revolutionary new weapons detection system (n.d.). https://yatesprotect.com/products/ ceia-opengate%E2%84%A2-a-revolutionary-new-weapons-detection-system.

21. How Opengate can improve your campus weapons screening process (n.d.) Campus Safety Magazine.

22. Internal data, Qlik Philly School Experience Survey Application, Accessed May, 2023.

23. Listening and Learning: Teacher attendance, student attendance, and dropout prevention. Spring 2023. Internal document.

24. Gonzalez, R., & Komisarow, S. (2020). Community monitoring and crime: Evidence from Chicago’s Safe Passage Program. Journal of Public Economics, 191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104250.

25. Listening and Learning: Teacher attendance, student attendance, and dropout prevention. Spring 2023. Internal Document.

26. Internal data, Office of Student Rights and Responsibilities, provided May, 2023.

27. Pace, S. (2018). From correctional education to reentry: How formerly incarcerated youth can achieve better educational outcomes. Texas Journal on Civil Liberties & Civil Rights, 23(2), 127–143.

28. Kelchner, V.P., Evans, K., Brendell, K., Allen, D., Miller, C., & Cooper-Haber, K. (2017). The effect of a school-based transitional support intervention program on alternative school youth’s attitudes and behaviors. The Professional Counselor 7(2), 169–184.https://tpcjournal.nbcc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/169-184-Kelchner.pdf.

29. Blomberg, T.G., Bales, W.D., Mann, K., Piquero, A.R., & Berk, R.A. (2011). Incarceration, education and transition from delinquency. Journal of Criminal Justice, 39(4), 355–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2011.04.003.

30. Listening and Learning: Teacher attendance, student attendance, and dropout prevention. Spring 2023. Internal document.

31. Listening and Learning: Teacher attendance, student attendance, and dropout prevention. Spring 2023. Internal document.

32. Kelchner, V.P., Evans, K., Brendell, K., Allen, D., Miller, C., & Cooper-Haber, K. (2017). The effect of a school-based transitional support intervention program on alternative school youth’s attitudes and behaviors. The Professional Counselor 7(2), 169–184. https://doi:10.15241/vpk.7.2.169.

33. Van Eck, K., Johnson, S.R., Bettencourt, A., & Johnson, S.L. (2017). How school climate relates to chronic absence: A multi–level latent profile analysis. Journal of School Psychology, 61, 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2016.10.001.

34. Davis, J. R. & Warner, N. (2015). Schools matter: The positive relationship between New York City high schools’ student academic progress and school climate. Urban Education, 53(8), 959–980. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085915613544.

35. Eugene, D. R. (2020). A multilevel model for examining perceptions of school climate, socioeconomic status, and academic achievement for secondary school students. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 25(1), 79–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/10824669.2019.1670067.

36. Kraft, M. A., & Falken, G. T. (2020). Why school climate matters for teachers and students (EJ1257758). State Boards of Education report. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1257758.pdf.

37. Papay, J. & Kraft, M. A. (2017). Developing workplaces where teachers stay, improve, and succeed: Recent evidence on the importance of school climate for teacher success. Teaching in Context: How Social Aspects of School and School Systems Shape Teachers’ Development & Effectiveness, 15–35. Harvard Education Press.

38. Reitano, A., Park, J. & Wills, T. (2018). School climate and PSSA Performance in Philadelphia, 2016-2017. School District of Philadelphia, Office of Research and Evaluation. https://www.philasd.org/research/wp-content/uploads/ sites/90/2018/03/DWS-Climate-and-PSSA-Performance-Focus-Brief-March-2018.pdf.

39. Internal Data, Qlik Philly School Experience Survey Application, Accessed May, 2023.

40. Schlesinger, M., Karakus, M., Park, J. (2021). School-wide Positive Behavioral Interventions & Supports (PBIS): Five-year school-wide outcome. School District of Philadelphia. https://www.philasd.org/research/2021/09/14/ school-wide-positive-behavioral-interventions-and-supports-pbis-five-year-school-wide-outcome-trends/.

41. Lee, A., & Gage, N. A. (2020). Updating and expanding systematic reviews and meta‐analyses on the effects of school‐wide positive behavior interventions and supports. Psychology in the Schools, 57(5), 783–804. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22336.

42. Pas, E. T., Ryoo, J. H., Musci, R. J., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2019). A state-wide quasi-experimental effectiveness study of the scale-up of school-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports. Journal of School Psychology, 73, 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2019.03.001.

43. Estrapala, S., Rila, A., & Bruhn, A. L. (2021). A systematic review of tier 1 PBIS implementation in high schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 23(4), 288–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300720929684.

44. Freeman, J., Kern, L., Gambino, A. J., Lombardi, A., & Kowitt, J. (2019). Assessing the relationship between the Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports Framework and student outcomes in high schools. Journal of At-Risk Issues, 22(2), 1–11. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1231342.pdf.

45. Freeman, J., Simonsen, B., McCoach, D. B., Sugai, G., Lombardi, A., & Horner, R. (2016). Relationship between school-wide positive behavior interventions and supports and academic, attendance, and behavior outcomes in high schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 18(1), 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300715580992.

46. Durlak, J. A., Mahoney, J. L., & Boyle, A. E. (2022). What we know, and what we need to find out about universal, school-based social and emotional learning programs for children and adolescents: A review of meta-analyses and directions for future research. Psychological Bulletin, 148(11-12), 765–782. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000383.

47. Taylor, R., Oberle, E., Durlak, J. A., & Weissberg, R. P. (2017). Promoting positive youth development through school-based social and emotional learning interventions: A meta-analysis of follow-up effects. Child Development, 88(4), 1156–1171. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12864.

48. Todić, J., Cubbin, C., Armour, M., Rountree, M., & González, T. (2020). Reframing school-based restorative justice as a structural population health intervention. Health & Place, 62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2020.102289.

49. Larson, S., Chapman, S., Spetz, J., & Brindis, C. (2017). Chronic childhood trauma, mental health, academic achievement, and school-based health center mental health services. Journal of School Health 87(9), 675–686. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12541.

50. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.) Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS). https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/index.htm.

51. The School District of Philadelphia (SDP) administered the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) to 1,351 randomly selected high school students from 30 Philadelphia public schools in the fall of 2021. Results are considered representative of the entire District. https://www.philasd.org/research/2021/10/21/summary-of-student-responses- from-the-2021-philadelphia-youth-risk-behavior-survey/.

52. Internal data, Qlik Philly School Experience Survey Application, Accessed May, 2023.

53. Reitano, A., McCrossan, E., Fornaro, E., Pylvainen, H., Lesnick, J., and Wolford, T. (2023). Highlights of key findings from the Superintendent’s Listening and Learning Tour. School District of Philadelphia. https://www.philasd.org/ research/2023/01/23/highlights-of-key-findings-from-the-superintendents-listening-and-learning-tour/.

54. Regional Education Laboratory Appalachia & Cross-State Collaborative to Support Schools in the Opioid Crisis. (2021). Menu of Trauma-Informed Programs for Schools [Handout]. Institute of Education Sciences. https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs/regions/appalachia/events/materials/04-8-20-Handout2_menu-trauma-informed- programs-for-schools.pdf.

55. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.) Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS). https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/index.htm.

56. The School District of Philadelphia (SDP) administered the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) to 1,351 randomly selected high school students from 30 Philadelphia public schools in the fall of 2021. Results are considered representative of the entire District. https://www.philasd.org/research/2021/10/21/summary-of-student-responses- from-the-2021-philadelphia-youth-risk-behavior-survey/.

57. Internal data, Qlik Philly School Experience Application, Accessed May, 2023.

58. Dandridge, S. (2020). Improving school health services for children in Philadelphia: An evaluation report for the School District of Philadelphia. Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia PolicyLab. https://policylab.chop.edu/tools-and- memos/improving-school-health-services-children-philadelphia-evaluation-report-school.

59. Internal data, Qlik School Employee Hiring Application, Accessed May, 2023.

60. Yoder, C. M. (2020). School nurses and student academic outcomes: An integrative review. Journal of School Nursing, 36(1), 49–60. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1059840518824397.

61. Pennsylvania Department of Education. (n.d.). Full-time school nurses for the management of students with asthma. Pennsylvania Evidence Resource Center. https://www.evidenceforpa.org/strategies/full-time-nurses- for-students- with-asthma.

62. Moricca, M. L., Grasska, M. A., Marthaler, M. B., Morphew, T., Weismuller, P. C., & Galant, S. P. (2013). School asthma screening and case management: Attendance and learning outcomes. The Journal of School Nursing, 29(2), 104–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059840512452668.

63. American Telemedicine Association. (2021). A framework for eliminating health disparities using telehealth. https://www.americantelemed.org/resource/research/.

64. Reynolds, C. A. and Maughan, E. D. (2015). Telehealth in the school setting: An integrative review. Journal of School Nursing 31(1) 44-53.

65. Hickson, M., Ettinger de Cuba, S., Weiss, I., Donofrio, G., & Cook, J. (n.d.). Too hungry to learn: Food insecurity and school readiness. Children’s HealthWatch. https://www.childrenshealthwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/ toohungrytolearn_report.pdf.

66. Weinstein, S., Hawes, P., Fornaro, E., & McCrossan, E. (2022). Household food insecurity in the School District of Philadelphia. School District of Philadelphia, Office of Research and Evaluation. https://www.philasd.org/research/ wp-content/uploads/sites/90/2022/04/Food-Insecurity-in-SDP-2020-21-April-2022.pdf.

67. Weinstein et al (2022).

68. Reitano, A., McCrossan, E., Fornaro, E., Pylvainen, H., Lesnick, J., and Wolford, T. (2023). Highlights of key findings from the Superintendent’s Listening and Learning Tour. School District of Philadelphia. https://www.philasd.org/ research/2023/01/23/highlights-of-key-findings-from-the-superintendents-listening-and-learning-tour/.

69. Listening and Learning: Teacher attendance, student attendance, and dropout prevention. Spring 2023. Internal document.

70. Internal data, Qlik Philly School Experience Survey Application, Accessed May 2023.

71. Fornaro, E. G., McCrossan, E., Hawes, P., Erdem, E., & McLoughlin, G. M. (2022). Key determinants to school breakfast program implementation in Philadelphia public schools: Implications for the role of SNAP-Ed. Frontiers in Public Health 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.987171.

72. Hartline-Grafton, H. (2019). School meals are essential for student health and learning. Food Research Action Center. https://frac.org/wp-content/uploads/School-Meals-are-Essential-Health-and-Learning_FNL.pdf.

73. Cohen, J.F.W., Hecht, A. A., McLoughlin, G. M., Turner, L., & Schwartz, M. B. (2021). Universal school meals and associations with student participation, attendance, academic performance, diet quality, food security, and body mass index: A systematic review. Nutrients 13(3), 911-952. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030911.

74. Adolphus, K., Lawton, C. L., & Dye, L. (2013). The effects of breakfast on behavior and academic performance in children and adolescents. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 7. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/ fnhum.2013.00425/full.

75. Philadelphia Evidence Resource Center (2021). Breakfast in the classroom. https://www.evidenceforpa.org/ strategies/breakfast-in-the-classroom.

76. Anderson, M. L., Gallagher, J., & Ritchie, E. R. (2017, March). School lunch quality and academic performance (NBER Working Paper No. 23218). https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w23218/w23218.pdf.

77. Tkatch, C., Erdem-Akcay, E. and Cassar, E. (2019). Expanding school breakfast participation, 2017-2018. School District of Philadelphia, Office of Research and Evaluation. https://www.philasd.org/research/wp-content/ uploads/sites/90/2019/01/Expanding-School-Breakfast-Participation-2017-18-Research-Brief-January-2019.pdf.

78. Fornaro, E. G., McCrossan, E., Hawes, P., Erdem, E., & McLoughlin, G. M. (2022). Key determinants to school breakfast program implementation in Philadelphia public schools: Implications for the role of SNAP-Ed. Frontiers in Public Health 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.987171.

79. Fornaro, E. G., McCrossan, E., Hawes, P., Erdem, E., & McLoughlin, G. M. (2022). Key determinants to school breakfast program implementation in Philadelphia public schools: Implications for the role of SNAP-Ed. Frontiers in Public Health 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.987171.

80. Hartline-Grafton, H. (2019). School meals are essential for student health and learning. Food Research Action Center.https://frac.org/wp-content/uploads/School-Meals-are-Essential-Health-and-Learning_FNL.pdf.

81. Bullying in schools. Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia: Center for Violence Prevention. https://violence.chop.edu/bullying-schools.

82. Internal data, Qlik Philly School Experience Survey Application, Accessed May 2023.

83. Salmon, G., James, A., & Smith, D. M. (1998). Bullying in schools: self reported anxiety, depression, and self esteem in secondary school children. BMJ 317, 924-925. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.317.7163.924.

84. Listening and Learning: Teacher attendance, student attendance, and dropout prevention. Spring 2023. Internal document.

85. Massey, W. V., Perez, D., Neilson, L., Thalken, J., & Szarabajko, A. (2021). Observations from the playground: Common problems and potential solutions for school-based recess. Health Education Journal, 80(3), 313-326. https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896920973691.

86. Fortson, J., James-Burdumy, S., Bleeker, M., Beyler, N., London, R. A., Westrich, L., Stokes-Guinan, K., & Castrechini, S. (2013). Impact and implementation findings from an experimental evaluation of playworks effects on school climate, academic learning, student social skills and behavior. Mathematica Policy Research. https://www.mathematica.org/ publications/impact-and-implementation-findings-from-an-experimental-evaluation-of-playworks-effects-on-school-climate-academic-learning-student-social-skills-and-behavior.

87. Negus, S. & Karakus, M. (2018). Playworks TeamUp Model evaluation: Year 2 Report. School District of Philadelphia, Office of Research and Evaluation. https://www.philasd.org/research/wp-content/uploads/sites/90/2018/08/ EvaluationReport2018_-Playworks_Final.pdf.

Priority Area 2

Priority Area 2

Partner with families and community

To live our core values of trust and collaboration, the District must foster trusting relationships with students, families, staff, and the entire Philadelphia community through transparent communication and frequent opportunities for partnership. Students, families, and staff expect the District to provide necessary information in an accessible and timely manner and to offer consistent opportunities for engagement to join in our work. Community partners expect clarity, consistency, and access to information to support relationships between the District and the Philadelphia community.

Forging strong partnerships and creating clear collaborative structures between the District and our broader community will enable us all to collectively support accelerated student achievement. Through the implementation of these Strategic Actions, families, students, staff, and community members will have greater access to information and timely responses, expanded access to enriching and well-rounded co-curricular opportunities, and new structures for collaboration with the Superintendent and District as a whole.

Strategic Actions

2.1 Launch a two-way communications system with multilingual capabilities to improve communications with families and the community.

2.2 Update the District and school websites.

Why is this urgent?

Survey data shows that stakeholders believe one of Dr. Watlington’s first priorities should be communication and engagement. During Listening and Learning sessions, families voiced that trying to communicate with the District can be frustrating because it is unclear who to contact about their concerns, and issues are not always addressed in a timely manner. When feedback is sought, it often feels performative or like “lip service” rather than a true opportunity to provide meaningful input. Stakeholders believe there is a lack of transparent communication, particularly around logistics, schedule changes, capital project planning, and work order processes, which makes planning difficult for families and school leaders. Similarly, members of the Violence Impacting Schools working group identified shortcomings in the way the District communicates about community safety and violent incidents. This results in a lack of trust between families and the District. District students and their families speak a variety of languages, and it is critical that systems of communication are accessible to all families in their preferred language.

Why these strategies?

Clear and open communication is critical for establishing trusting relationships between families and schools, which fosters greater engagement. Students with engaged parents and guardians are more likely to earn higher grades and test scores, attend school regularly, have better social skills, and graduate and go on to postsecondary education. Connecting students, families, and schools with community assets can promote student achievement, expand access to health and wellness resources, and help break the cycle of poverty.

Aligns with: Guardrail 3; Transition Team Recommendations

2.3 Launch a Superintendent’s parent and guardian advisory group that reflects our diversity, including parents and guardians of underserved students, students with disabilities, and English Learners.

2.4 Launch a Superintendent’s teacher advisory group.

2.5 Launch a Superintendent’s principal advisory group.

2.6 Relaunch a Superintendent’s student advisory group.

2.7 Launch a Superintendent’s advisory group with external stakeholders and community partners.

Why is this urgent?

During Listening and Learning sessions, parents and guardians, teachers, principals, students, and community members shared that they want more opportunities to have their opinions and experiences heard and considered in decision-making. Stakeholders also feel that decisions made by the Central Office sometimes feel abrupt and arbitrary, and that decisions should be made based on shared values. On the annual survey, only 11% of teachers strongly agreed that they feel respected by the District, and only 22% of principals strongly agreed that they feel respected by the District.

Why these strategies?

A collaborative decision-making model means that families, students, and school staff are included in the decision-making processes that directly impact their work and learning. This structure enhances the ability of schools to respond to problems and opportunities, improves relationships between leaders and key stakeholders, increases satisfaction and morale, facilitates better decision making by eliciting more viewpoints, and helps reduce stress and burnout. School-community partnerships can enable the expansion of services and resources for students, and are often most effective when community partners and districts have a strong relationship based on collaboration and respect.

Aligns with: Guardrail 3; Transition Team Recommendations

2.8 Create a database of all District partnerships, their alignment to the strategic plan, and impact.

Why is this urgent?

Schools reported a total of 1,646 external support programs in 2019-20, provided by 1,050 organizations, with an average of 15 programs per school. The data suggests that current school partnerships are not equitably distributed among schools, nor are they always meeting the critical needs of schools. During Listening and Learning sessions, stakeholders discussed how community

Priority Area 2 partnerships are a key way to bring in more resources; however, there is a need to improve coordination between the District, schools,

and community partners. Additionally, stakeholders shared significant concerns about managing partnerships and explained that they do not have the capacity to manage all the available partnerships that could benefit their students and communities. Thirty-two schools reported that they had a partnerships coordinator. School leaders reported that limited staff capacity to establish and/or coordinate partner programs was a challenge to partnership development.

Why this strategy?

Improving schools involves addressing the social and economic challenges that students and their families face. Building partnerships strengthens the capacity of schools to respond to student needs. Partnerships can enhance students’ social, emotional, and intellectual development. However, with limited time and numerous needs, it is the responsibility of the District to ensure that partnerships are properly aligned to the needs of schools and they are meeting the agreed upon expectations in terms of operations and outcomes.

Aligns with: All Goals and Guardrails; Transition Team Recommendations

2.9 Relaunch Parent University to provide resources and support to families and community.

Why is this urgent?

Census data shows that almost 22% of Philadelphians are living below the poverty line, 13% do not have a high school diploma, and only 33% have a bachelor’s degree or higher. This speaks to the need for adult education programming. Additionally, Listening and Learning feedback highlighted that there is a lack of trust between families and the District; engaging parents and guardians in workshops and training is a way to increase engagement, which can help to build positive relationships and repair trust.

Why this strategy?

Participation in adult education programming increases access to the knowledge and skills that enable social mobility and increased democratic participation. Furthermore, a study found that districts play an important role in providing adult education, as they are responsible for providing over half of the adult education programming available across the nation. Not only can participating in a parent university have positive outcomes for parents and guardians, but research has found that students can benefit when their parents and guardians have the skills and resources to be engaged in their education.

Aligns with: Guardrails 1 and 3

2.10 Establish a parent ambassador role (with paid stipends).

Why is this urgent?

During Listening and Learning sessions, parents and guardians expressed how they have lost trust in the District and are often frustrated by the lack of communication about important aspects of their child’s education. Currently, schools share Family Liaisons that report to the Office of Family and Community Engagement. A way to improve positive relationships with parents and guardians and improve communication is to ensure that all schools have a dedicated liaison that can focus on a single school community and connect parents and guardians with their schools and the District.

Why this strategy?

Parent ambassadors are members of the school community that have established relationships with parents and guardians. As part of a larger initiative to increase parent/guardian engagement with schools, parent ambassadors can be a way to build parent/guardian networks across school communities as well as spread the word about district-provided support and resources for parents and guardians.

Aligns with: Guardrails 1 and 3

2.11 Evaluate and replicate successful Community School models.

Why is this urgent?

Community Schools provide resources that can address many of the barriers that our students and families face. In addition to providing students with wrap-around services, such as health centers, before and after school activities, and social and employment services, community schools serve to enrich students’ academic experiences by connecting them with mentoring, internships, and employment opportunities. These services were all mentioned as desirable to help meet the needs of our students and their families during Listening and Learning sessions.

Why this strategy?

National research has shown that students who attend community schools have increased access to health care and higher graduation rates. A study of the Community School Initiative in Philadelphia during its first year found that there were some system level challenges to implementation at the school level, but stakeholders were satisfied with the initiative. Now that the Community School Initiative is in its sixth year, an updated evaluation would provide additional information about how community schools in Philadelphia are benefiting students and families, and how to replicate successful practices across community school sites.

Aligns with: All Goals, Guardrails 1 and 3

Supporting Research

88. Reitano, A., McCrossan, E., Fornaro, E., Pylvainen, H., Lesnick, J., and Wolford, T. (2023). Highlights of key findings from the Superintendent’s Listening and Learning Tour. School District of Philadelphia. https://www.philasd.org/ research/2023/01/23/highlights-of-key-findings-from-the-superintendents-listening-and-learning-tour/.

89. Reitano, A., McCrossan, E., Fornaro, E., Pylvainen, H., Lesnick, J., and Wolford, T. (2023). Highlights of key findings from the Superintendent’s Listening and Learning Tour. School District of Philadelphia. https://www.philasd.org/ research/2023/01/23/highlights-of-key-findings-from-the-superintendents-listening-and-learning-tour/.

90. Bryk, A. S., & Schneider, B. (2002). Trust in schools: A core resource for improvement. Russell Sage Foundation. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7758/9781610440967.

91. Constantino, S. (2007). Keeping parents involved through high school. The Education Digest 73(1), 57-61; Epstein, J. L. (2010). School/Family/Community Partnerships: Caring for the Children We Share. Phi Delta Kappan, 92(3), 81–96, https://doi.org/10.1177/003172171009200326.

92. Drummond, K. & Stipek, D. (2004) Low income parents’ beliefs about their role in children’s academic learning. The Elementary School Journal, 104(3), 197–213. https://doi.org/10.1086/499749.

93. Hoover-Dempsey, K. V. & Sandler, H. M.(1997). Why do parents become involved in their children’s education?, Review of Educational Research, 67(1) 3–42. https://doi.org/10.2307/1170618.

94. Horvat, E. M. (2011). Pioneer parents and creating pathways for involvement: A historical case study of school change and collective parental involvement. In C. Hands & L. Hubbard (Eds.), Including Families and Communities in Urban Education (pp. 161–188). Information Age Publishing.

95. Moore, K. A. & Emig, C. (2014). Integrated student supports: A summary of the evidence base for policymakers [White paper]. Child Trends. https://cms.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/2014-05ISSWhitePaper3.pdf.

96. Dryfoos, J. G. (2000). Evaluation of community schools: Findings to date. Coalition for Community Schools. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED450204.pdf.

97. Moore, K. (2014). Making the grade: Assessing the evidence for integrated student supports. Child Trends. https://cms.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/2014-07ISSPaper2.pdf.

98. Reitano, A., McCrossan, E., Fornaro, E., Pylvainen, H., Lesnick, J., and Wolford, T. (2023). Highlights of key findings from the Superintendent’s Listening and Learning Tour. School District of Philadelphia. https://www.philasd.org/ research/2023/01/23/highlights-of-key-findings-from-the-superintendents-listening-and-learning-tour/.

99. Internal data, Qlik Philly School Experience Application, Accessed May, 2023.

100. Clark, S. N. & Clark, D. C. (2002). Collaborative decision making: A promising but underused strategy for middle School Improvement. Middle School Journal, 33(4), 52–57, https://doi.org/10.1080/00940771.2002.11494684.

101. Liontos, L. B. (1993). Shared decision-making. Oregon School Study Council, 37(2). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED363969.pdf.

102. Sanders, M. G. (2006). Building school–community partnerships: Collaboration for student success. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

103. Carter, K. (2021). School support census 2019-20 report. School District of Philadelphia, Office of Research and Evaluation. https://www.philasd.org/research/wp-content/uploads/sites/90/2021/08/School-Support-Census-2019-20-Report-July-2021.pdf.

104. Reitano, A., McCrossan, E., Fornaro, E., Pylvainen, H., Lesnick, J., and Wolford, T. (2023). Highlights of key findings from the Superintendent’s Listening and Learning Tour. School District of Philadelphia. https://www.philasd.org/ research/2023/01/23/highlights-of-key-findings-from-the-superintendents-listening-and-learning-tour/.

105. Reitano, A., McCrossan, E., Fornaro, E., Pylvainen, H., Lesnick, J., and Wolford, T. (2023). Highlights of key findings from the Superintendent’s Listening and Learning Tour. School District of Philadelphia. https://www.philasd.org/ research/2023/01/23/highlights-of-key-findings-from-the-superintendents-listening-and-learning-tour/.

106. Internal Data, Qlik School Support Census Application, Accessed May, 2023.

107. Reitano, A., McCrossan, E., Fornaro, E., Pylvainen, H., Lesnick, J., and Wolford, T. (2023). Highlights of key findings from the Superintendent’s Listening and Learning Tour. School District of Philadelphia. https://www.philasd.org/ research/2023/01/23/highlights-of-key-findings-from-the-superintendents-listening-and-learning-tour/.

108. Noguera, P. A. & Wells, L. (2011). The politics of school reform: A broader and bolder approach for Newark. Berkeley Review of Education, 2(1), 5–25. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1169709.pdf.

109. Sanders, M. G. (2006). Building school–community partnerships: Collaboration for student success. Corwin Press. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452224831.

110. U.S. Census Bureau. Population estimate for Philadelphia County, July 1, 2022. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/philadelphiacountypennsylvania.

111. Reitano, A., McCrossan, E., Fornaro, E., Pylvainen, H., Lesnick, J., and Wolford, T. (2023). Highlights of key findings from the Superintendent’s Listening and Learning Tour. School District of Philadelphia. https://www.philasd.org/ research/2023/01/23/highlights-of-key-findings-from-the-superintendents-listening-and-learning-tour/.

112. Cervero, R. & Wilson, A. (2001). Power in practice: Adult education and the struggle for knowledge and power in society. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc.

113. Tamassia, C., Lennon, M., Yamamoto, K., & Kirsch, I. (2007). Adult education in America: A first look at results from the adult education program and learner surveys. Education Testing Service.

114. Mendez, J. L. and Swick, D. C. (2018). Guilford Parent Academy. Education and Treatment of Children (41)2, 249-268.

115. Listening and Learning: Teacher attendance, student attendance, and dropout prevention. Spring 2023. Internal document.

116. Mendez, J. L. and Swick, D. C. (2018). Guilford Parent Academy. Education and Treatment of Children (41)2, 249-268.

117. Moore, K. & Ernig, C. (2014). Integrated student supports: A summary of the evidence base for policymakers. Child Trends Publication #2015-05.

118. Coalition for Community Schools. Community schools: Partnerships for excellence. Institute for Education Leadership. http://www.communityschools.org/assets/1/Page/partnershipsforexcellence.pdf.

119. Lubell, E. (2011). Building community schools: A guide for action. National Center for Community Schools, The Children’s Aid Society.

120. Listening and Learning: Teacher attendance, student attendance, and dropout prevention. Spring 2023. Internal document.

121. IFC International (2010). Communities in schools national evaluation: Five Year Summary. https://www.theoryofchange.org/wp-content/uploads/toco_library/pdf/2010_-_ICF_International_-_Communities_In_Schools_National_Evaluation_Five_Year_Summary_Report.pdf.

122. Dryfoos, J. (2000). Evaluation of community schools: Findings to date. Washington, DC: Coalition for Community Schools.

123. Duffy, M. and McCarty, A. (2018). The community school initiative: Year 1 Report. Research for Action. https://www.researchforaction.org/research-resources/k-12/the-philadelphia-community-schools-initiative-year-1- evaluation/.

Priority Area 3

Priority Area 3

Accelerate academic achievement

The District’s primary goal is to provide the learning environments and supports necessary for all students to develop foundational academic skills and graduate college and career ready. We also know that high-quality, well-supported teachers and principals are imperative to our students’ academic achievement, especially in math, English Language Arts, and science. As such, we must provide all schools with rigorous, standards-aligned, culturally relevant curricula and prepare all leaders and educators to use high- quality and inclusive instructional tools. Further, we can expand equitable access to various course offerings that fit our students’ interests and goals, and create opportunities for students to receive additional support that meets their unique learning needs. When these Strategic Actions are implemented, all students will attend schools that enable them to succeed.

Strategic Actions

3.1 Inventory and improve access to high quality Pre-K programs for underserved populations.

Why is this urgent?

According to Philadelphia’s Commission on Universal Pre-Kindergarten only 1 in 3 of Philadelphia’s three- and four- year olds has access to affordable, quality Pre-K. According to Pre-K for PA, 37% of eligible children in Philadelphia do not have access to high-quality, publicly funded Pre-K.

Why this strategy?

Decades of research suggest several immediate benefits related to participation in high quality Pre-K, including increases in reading readiness and critical thinking, improved self-control and social skills, and higher classroom confidence. Recent research finds that students who participated in high quality Pre-K are more likely to enroll in advanced high school coursework, attend school regularly, and graduate on time. High quality Pre-K programs are defined by those that are aligned with rigorous and culturally appropriate learning standards, use a strong curriculum, employ highly trained teachers, provide adequate professional development, maintain a low child-staff ratio, screen and refer students for health related barriers to learning, and have a teacher observation and feedback system in place.

Aligns with: Goals 1-3

3.2 Purchase and implement standards-aligned core instructional resources for math (in partnership with teachers, school leaders, and parents and guardians).

3.3 Purchase and implement standards-aligned core instructional resources for English Language Arts (ELA), with a focus on the Science of Reading (in partnership with teachers, school leaders, and parents and guardians).

3.4 Purchase and implement standards-aligned core instructional resources for science (in partnership with teachers, school leaders, and parents and guardians).

Why is this urgent?

In 2021-22, 17% of grade 3-12 students were proficient or advanced in math on the end-of-year state standardized assessments (PSSA Math and Keystone Algebra 1 exams); 36% of grade 3-12 students were proficient or advanced in ELA on the state end-of-year standardized assessments (PSSA ELA and Keystone Literature exams); and 33% of grade 4 and 8-12 students were proficient or advanced in science on the state end-of-year standardized assessments (PSSA Science and Keystone Biology exams). Teachers and school leaders have voiced that clear and consistent curricular resources are needed across schools. A curriculum audit also raised the need for a district-wide academic program that is aligned to Common Core standards and that is clearly based on a theory of action about how to improve student achievement.

Why these strategies?

The use of a rigorous curriculum in combination with high quality materials can positively impact the quality of classroom instruction and student achievement.

Number competency in Kindergarten and first grade strongly and significantly predict later math achievement, and in some cases reading achievement, even when controlling for differences in other academic areas, behavior, cognitive development, family characteristics, and home environment. Students who are not skilled readers by the end of third grade are unlikely to graduate high school. Structured Literacy, based on the Science of Reading, is the most effective approach to teaching students to learn to read. Research suggests the majority of students in general education classrooms, and nearly all students with specialized needs, benefit from this approach to literacy. Research has shown that students who participate in design-based or project-based science curricular programming had more developed higher order thinking skills (critical thinking, problem solving, and application) and higher proficiency levels on the state science assessment than their peers who participated in traditional science courses. This strategy will ensure we use these research- based approaches to teaching math, reading, and science.

Aligns with: Goals 1-4; Transition Team Recommendations

3.5 Pilot evidence-based high impact tutoring in 6 to 8 schools.

Why is this urgent?

The COVID-19 pandemic had a negative impact on student achievement; one study estimates that students lost four months of learning by the end of the 2020-21 school year. Many District students are not meeting grade level standards, and require opportunities for accelerated learning to catch up.

Why this strategy?

High impact tutoring can be effective at advancing student achievement when delivered with fidelity. Important aspects to consider when selecting a tutoring approach are when and how often the tutoring occurs, the quality of the materials used, and the extent to which tutors receive the necessary training and support. A study of Saga Education by the University of Chicago found that students who received tutoring with fidelity learned up to 2.5 years worth of math in one year.

Aligns with: Goals 1-3

3.6 Pilot a year-round and extended-day school calendar in up to 10 schools.

Why is this urgent?

Many SDP students are not meeting grade level standards, and require opportunities for accelerated learning to catch up. During Listening and Learning sessions, students and teachers discussed wanting more opportunities to participate in programming before and after the traditional school day and highlighted the benefits of spending structured time with their peers beyond the hours of the current school day.

Why this strategy?

Participating in high quality out-of-school time programming or extracurricular activities is tied to the improvement of a variety of outcomes for students, including math and reading achievement, physical and mental health, school attendance, promotion, graduation, college enrollment, and increased civic engagement. External research also suggests summer and after school programming can be effective in accelerating learning, provided there are small staff-to-student ratios, and adequate dosage in terms of hours. Incorporating these types of opportunities into the day-to-day school experience, rather than as “extra” or “additional” supports that students must sign up for, will likely result in similar positive effects for students.

In the United States, “year-round schooling” does not mean that students are in school for more days out of the year. Rather, the typical number of required school days, which is 180 in Pennsylvania, is spread out over the year so that there are more frequent, shorter breaks instead of having the extended summer break. For example, some schools in California that have a year-round-schooling model have a “60/20 calendar,” which means there are 60 days of instruction followed by 20 days of vacation.

Research on these types of year-round school models have found no positive effects on student achievement. Taken together, the research suggests that simply reallocating seat time across the year is not an adequate strategy for improving student achievement. Changes to the calendar must be paired with opportunities for students to participate in enriching and meaningful learning experiences that are not typically incorporated into the traditional school year due to time constraints.

Aligns with: Guardrail 2

3.7 Pilot learn to swim programs in different parts of the city in alignment with the curriculum.

Why is this urgent?

Drowning is the second leading cause of unintentional injury death for children ages 5-14 in the United States. Black/African American and Latino urban youth report having poor swimming skills at higher rates than their white peers, putting them at greater risk of swimming related injury or death.

Why this strategy?

When children and adults participate in swimming lessons, their risk of drowning is reduced.

Aligns with: Guardrails 1, 2, and 4

3.8 Audit and improve compliance with Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) and expand supports for English Learners.

Why is this urgent?

The special education population in the District is large and diverse. In 2022-23, more than 18,000 students are receiving specialized education supports across nine different types of programs. The District also serves a large and diverse population of English Learners (EL). In 2022-23, there were more than 20,000 EL students with over 150 different home languages. This represents an increase of 3,000 ELs over the prior school year. The EL population includes students with specialized needs, including newcomers, students with limited or interrupted formal education, and long-term English Learners.

Why this strategy?

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act “…requires public school systems to develop appropriate Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) for each child. The specific special education and related services outlined in each IEP reflect the individualized needs of each student.” When districts are compliant with IEPs, students are receiving the appropriate supports for learning and are more likely to have improved outcomes. Similarly, when districts promote challenging activities with the right support for English Learners, students are more likely to achieve English proficiency and engage in grade level content.

Aligns with: All Goals; Transition Team Recommendations

3.9 Provide more support to teachers in the areas of content knowledge, student engagement, and culturally and linguistically relevant instructional practices.

Why is this urgent?

During Listening and Learning sessions, stakeholders voiced that there is a need for more Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion professional development and training for teachers and staff. On the annual survey, 47% of teachers said that a lack of support for teaching special education students was a challenge; 38% said lack of support for teaching English Learners was a challenge; and 70% said range of student abilities was a challenge to student learning. On the annual survey, less than half (45%) of students said that their school meets their learning needs most or all of the time.

Why this strategy?

Research shows that special populations of students are best served when teachers are engaged with professional development that “builds educator capacity to understand how gender, race, class, language, ethnicity, and ability differences are perceived and treated in the institution and influenced by implicit bias and micromessaging.” Additionally, teachers need support to use effective scaffolds to engage students in rigorous instruction; promote quality interactions, critical thinking, and discourse; use formative assessment to assess progress; and honor students’ home languages, assets, and experiences in the classroom.

Aligns with: All Goals, Guardrail 4; Transition Team Recommendations

3.10 Establish a baseline standard for which courses, programs, academy models, and co-curricular opportunities will be offered in all schools (Elementary, Middle, and High School).

Why is this urgent?

In Listening and Learning sessions, students voiced they would like access to a wider variety of courses and electives that are more aligned with their interests, are relevant to their lives, and prepare them for their future. On the annual survey, fewer than 4 in 10 students reported that they learn interesting things in their classes most or all of the time.Stakeholders also believe that art and music classes should be available to all students each year.

Additionally, feedback was given that rigorous academic courses should be offered in all schools, not just in criteria-based schools. In the 2021-22 school year, 61% of District high schools offered Advanced Placement (AP) courses, 11% offered International Baccalaureate (IB) courses, and 43% offered dual enrollment or college level courses. Many of the new Act 158 graduation pathways also depend on these opportunities. Currently, 34 out of 130 (26%) schools that serve 8th grade students offer Algebra 1. These schools are mostly concentrated in Center City and Northeast Philadelphia.

Why this strategy?

The intensity and quality of a student’s high school curriculum is a strong predictor of bachelor’s degree completion. For example, a high score on the AP final or IB final exam in any AP or IB course, or participation in dual enrollment programming, is positively correlated with college enrollment and persistence rates. Research shows that students who enter career academies are more likely to earn a diploma or General Educational Development (GED) credential, have more post-secondary opportunities, and higher wages than similar students who do not. Studies have also found that 9th Grade Academies can effectively support students’ transition to, and successful completion of, 9th grade. Academies are most successful when they implement the following with fidelity: have a dedicated space in the school building for 9th grade students; have a dedicated 9th grade teaching staff with regularly scheduled time for collaboration; and a dedicated 9th grade administrator. While the District currently supports 9th Grade Academies, they are implemented with varying degrees of fidelity.

Art and music education are also key factors in the success of students in school and beyond. There is a positive relationship between involvement in the arts and increased positive non-academic behaviors, including participating in student government, volunteering, voting, decreased delinquency and drug use, increased self-esteem, and more positive interactions with peers and adults. There is some evidence that suggests that learning a foreign language promotes knowledge acquisition for students. Additionally, since many of the most competitive colleges have language requirements, all schools should offer at least two years of a foreign language in addition to Spanish and French, languages that many District students already speak as their native language.

Algebra can be a “gatekeeper” to success in advanced math and in the job market, especially in STEM-related careers. However, it is important that this strategy be accompanied by increased rigor in pre-algebra courses, as research shows that if students enroll in Algebra I before they are ready, they may end up struggling with coursework, which can decrease the likelihood that they take higher level math.

Aligns with: All Goals, Guardrails 2 and 4; Transition Team Recommendations

3.11 Develop a project team to recommend optimal middle school design, programming, and facilities.

Why is this urgent?

According to Listening and Learning sessions with school leaders, in some cases, middle grade students are not properly prepared for the transition to high school. Specifically, leaders discussed: 1) inadequate investment in pre-algebra and literacy skills during middle school years; 2) a lack of exposure to career paths, high school options, and postsecondary opportunities; and 3) a lack of focus on preparing students for the social and operational aspects of high school.

Why this strategy?

Research suggests that there is no significant difference in the academic performance of middle school students who attend K-8 schools and those who attend true middle schools.However, students in middle grades are more likely to fall behind academically than students in younger grades and, if not properly identified and supported, risk being off track for high school graduation. What is most important is that the school is properly resourced to: 1) respond to the specific needs of middle school students, 2) deliver an instructional program that prepares students for the rigor of high school, and 3) develop a sense of attachment and belonging.

Aligns with: Goals 1, 3, and 4

3.12 Appoint an administrator to identify, audit, and improve access for underserved students to Career and Technical Education (CTE) and building trades programs across the city in alignment with regional workforce trends.

Why is this urgent?

In the spring of 2022, less than half (43%) of students in Career and Technical Education (CTE) programs passed their occupational competency tests, assessments of whether or not their skills meet industry standards. Performance varied across schools and CTE programs. However, during Listening and Learning sessions, teachers, community members, and parents and guardians said they would like to see more CTE and internship opportunities.

Why this strategy?

Career and Technical Education (CTE) provides students opportunities to personalize their education based on their career interests and unique learning needs. Compared to non-CTE students, CTE students are likely to graduate from high school on time, enroll in postsecondary education within two years of their expected high school graduation year, and have higher median annual earnings. Research done in the District mirrors these findings: participation in CTE is associated with higher graduation rates for students. Also, CTE students who do not meet promotion requirements in grades 10 or 11 are more likely to catch back up if they continue their CTE program. The District recently partnered with the Southern Regional Education Board (SREB) to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of all CTE programs from January 2023 through July 2025. The evaluation will identify strengths, areas for improvement, and best practices for each CTE program, ensure they are in alignment with local and regional workforce demands, and replicate model programs throughout the District.

Aligns with: Goals 4 and 5; Transition Team Recommendations

3.13 Expand 9th Grade On-Track (Success Networks) to reduce dropouts and increase four year graduation rates.

Why is this urgent?

In the spring of 2022, 29% of 9th grade students tested on grade level in ELA and 19% in math. Moreover, at the end of the 2021-22 school year, less than a third (27%) of 9th graders were firmly on track to graduate in four years. During Listening and Learning sessions, school leaders and students emphasized the importance of supporting students through the transition to high school so that they feel comfortable in a larger setting with new students and better understand academic expectations.

Why this strategy?

School District of Philadelphia data consistently shows that 9th Grade On-Track status is linked with on-time graduation. Research from Chicago shows that 9th Grade Success Networks have increased on-time graduation rates. The District can leverage and expand a promising existing program, that is modeled off of the program in Chicago, and established through a partnership with the Neubauer Foundation.

Aligns with: Goal 4

3.14 Hire an administrator to better coordinate a District-wide dropout reduction strategy.

Why is this urgent?

As of April 2023, over 3,600 District students in grades 7-12 dropped out of school. Not completing high school is associated with poor economic and health outcomes throughout life as well as an increased risk of incarceration.

Why this strategy?

Many of the reasons associated with dropping out are complex and require the coordination of services across offices and providers. Supportive interventions, such as mentoring and restorative practices, can have a positive effect on attitudes about school for students, especially those who are transitioning back from a long-term placement. This is important because students returning from long-term placement are at a high risk of dropping out and benefit from intense levels of adult support and service coordination, which schools do not always have the capacity to provide.

Aligns with: Goal 4 and Guardrail 1

3.15 Launch a financial literacy module for all high schools.

Why is this urgent?

Nearly 1 in 4 Philadelphians live below the poverty line and 12% live in deep poverty. Currently, 42 out of 73 District and Alternative schools serving students in grades 9-12 for which data is available offer a financial literacy course.

Why this strategy?